Wastewater Wonderland

Rim Country weather and its effect on wastewater treatment at Green Valley Water

By: Anna Van Zile

In the realm of wastewater treatment, Garrett Goldman, District Manager of Green Valley Water (GVW), is always looking to the future and technological updates while maintaining low rates for Payson residents. A forward-thinking, problem-solving, experienced Wastewater Reclamation Facility Plant Manager would ensure accomplishing this, but it is a challenging endeavor for a plant located in a rural Arizona community. Enter: Kalen Moore.

Enter: Kalen Moore

Kalen Moore began his post-secondary studies at Cal State, San Bernardino, as a physics major. Having grown tired of school, he found his way to the Eastern Municipal Water District (EMWD), servicing the city of Moreno Valley in Southern California. His dad, a maintenance manager at EMWD, suggested that Kalen volunteers around the plant to see if he might find the work interesting. Rather than volunteering, he was offered a temporary job and later hired at almost double the minimum wage. His experiences and training forced him out of physics and into biology, gathering certifications as a chlorine specialist on a Hazmat team; this included work with human remains and chemicals and a strong focus on observation training through “20 Sources of Information.” After 11 years at EMWD, Kalen, by then a family man, moved to Oregon, where he worked just over a year for Clean Water Services, processing up to eight times the amount of daily waste (100MGD) he had overseen previously.

During a family visit to Payson, Kalen dropped off his resume a day late for an opening that was closed. But four months later, his application resulted in an interview leading to his hiring as Green Valley Water’s Water Reclamation Facility (WRF) Grade IV Operator. Armed with years of experience working with EMWD’s 600 employees who processed 12.5 million gallons of wastewater daily for 250,000 residents. Green Valley Water employees process 1 million gallons a day for roughly 16,000 residents living in the Payson area. Kalen settled into a familiar yet very different job.

Rim Country Weather and its Effect On Wastewater Treatment

As Green Valley Water’s WRF Plant Manager, Kalen’s job responsibilities include maintaining the plant’s biological process, operating the equipment within the facility, and training and teaching the staff, all of which profoundly impact costs and savings for GVW and its customers.

Maintaining the plant’s biological process is the most important of these responsibilities. To accomplish this, Kalen works closely with the Lab Director, reviewing all wastewater sample data and identifying issues before they become problems. Though the amount of wastewater processed daily does not vary with the seasons despite the misperception that Payson visitors increase during summer more than winter, the aquatic ecosystem exhibits different characteristics in these seasons and must be treated accordingly. For instance, warm weather brings with it visible nuisances requiring treatment: mosquito and midge fly larvae (aka “redworms”) attack the mixed liquor suspended solids (a biomass-containing bacteria that treats the water). In particular, the redworms feed on helpful bacteria, which can cause a reduction in treatment and lead to a permit exceedance. The solution is Aquaback Xt, an EPA-certified biological treatment found naturally in soil. GVW adds to the aeration basins weekly to kill both types of larvae despite the redworms’ defense mechanism—forming cocoons as protection from the Aquaback Xt.

The warming weather presents another problem: decreased levels of phosphorus removal. Starting in the spring, Kalen stresses the system to increase the Phosphorus Accumulating Organisms (PAO) by gradually increasing dissolved oxygen in the water and decreasing the Sludge Retention Time (SRT). While the PAOs happily remove phosphorus from the system when it’s cooler, Glycogen Accumulating Organisms (GAO) exist in the same environment and compete with the PAO for the same food. Once the water temperature rises above 20ºC (68ºF), the GAO has an advantage over the PAO. To aid the PAO in the battle, the water environment has to be changed. GAO don’t like high pH, high dissolved oxygen, or cooler temperatures and are very slow growers (longer SRT). With the plant being manipulated over months, the PAO are abundant and continue removing phosphorus from the aeration basins, reducing the phosphorus level from 6-8 mg/L to less than 0.1 mg/L, an almost undetectable level that defies science. It’s easier to eliminate phosphorus by adding chemicals and continuously running blowers to cool the basins. Green Valley Water practices the natural and less costly route by using oxygen to maintain conditions from winter to summer.

The Transition from Summer to Winter

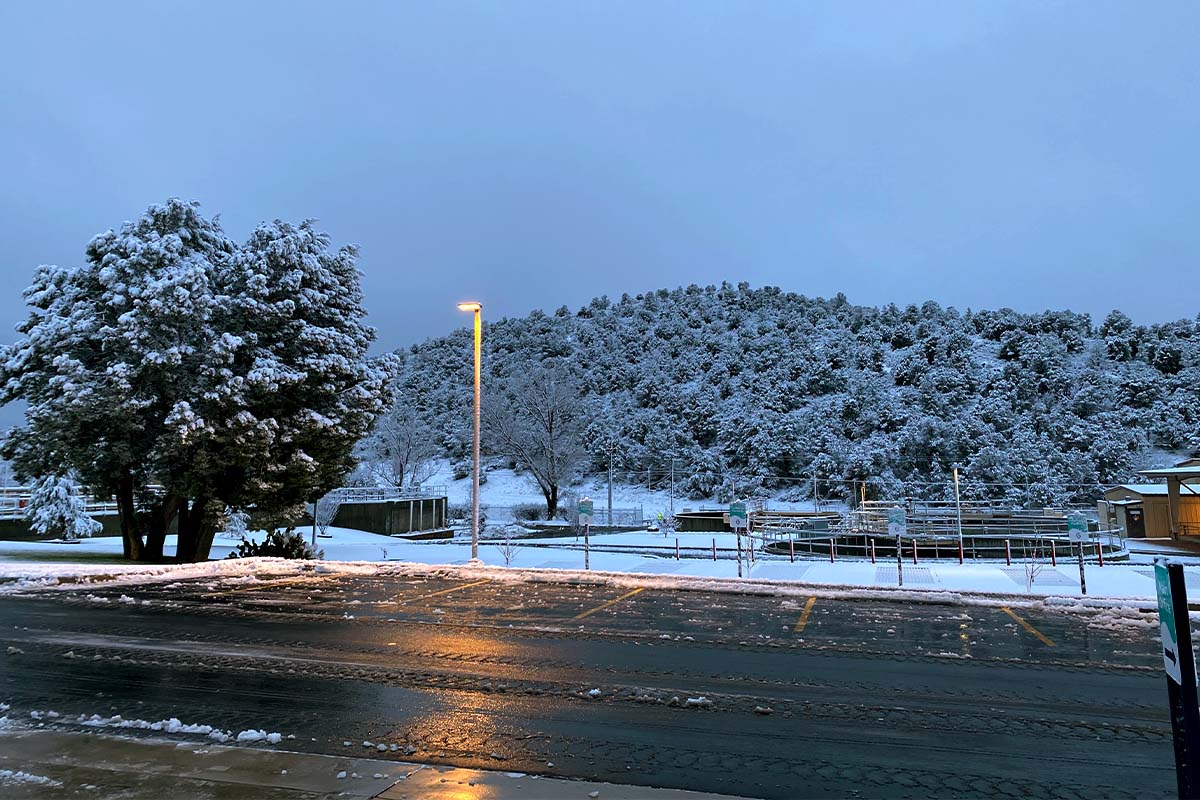

During the change from summer to winter, the plant no longer treats redworms and mosquito larvae; with the cooling weather, the PAO remains, and the GAO goes dormant. To help decrease the cost of treatment, the Dissolved Oxygen (DO) is lowered to save on electricity, and the SRT is increased to save on sludge hauling costs. The colder weather has a different impact on the plant. With snow comes the challenges of accessing the various parts of the plant. Operating the equipment within the plant is another of Kalen’s critical responsibilities. His primary concern is to inspect and ensure all equipment on campus is operationally sound. Events that occur outside the fence can have a significant impact on plant operations. For instance, one risk to the biological process is a washout of the “bugs” due to flooding rains. When this happens, the plant has to modify its operation, turning off mixers and creating a makeshift contact stabilization basin, retaining most of the bugs in the basin to reduce the Biochemical Oxygen Demand of the organic material in the wastewater. Two years ago, as much as 2.5 million gallons of water would enter the sanitary drains with heavy rains and snow melt, even though storm and sewer drains are not combined in Payson, AZ. Using the Geographical Information System, Collection System Maintenance workers located and repaired broken pipes, capped uncapped sewer cleanouts and placed stainless steel domes under manhole covers that water flowed over when it rained. By identifying and stopping rainwater from entering a relatively closed system, stormwater Inflow/Infiltration has been reduced to 100,000 gallons per day from millions a day. Increasing the line size would have been another costly solution to the rainwater problem.

Despite Kalen’s best efforts, along with the plant maintenance department, to prevent equipment failures through daily inspections, sometimes problems will occur. Even with redundancy built in, the belt press polymer pump and its backup went down the same weekend this year. A temporary pump repair was made to get through the next couple of days, while a replacement pump was due to arrive two days later. Without being able to run the belt press, the mixed liquor suspended solids would become old, causing phosphorus to increase and treatment to decrease. But even the smallest of parts can have a significant impact on water treatment. The final step of the biological process is the water’s exposure to Ultraviolet light. Each equipped with a computer chip has a life of more than 14,000 hours, with alarms sounding to announce its end-of-life. Ultrasonic sensors activate U.V. bulbs based on the water level so that only the submerged bulbs come on. And though it may be easier to replace all bulbs on a panel at once, they are replaced as they reach their hours, still at $20,000.00 a year. As much as possible, Green Valley Water is always a good steward of its customers’ dollars.

In addition to maintaining the biological process and operating the plant equipment, Kalen is also responsible for training the staff. On the one hand, training refers to Kalen reviewing Standard Operating Procedures across all aspects of the plant and writing manuals that provide step-by-step directions allowing anyone to perform a task, whether taking a clarifier online or offline or changing a U.V. bulb. These manuals did not exist before his arrival, yet they ensure the ability to keep the plant running smoothly. On the other hand, Kalen trains all employees, offering classes once or twice a month for different certifications and process knowledge. This requires teaching employees math, such as Hydraulic Loading Rates and Volatile Solids Reduction, knowing that Celsius is the industry standard of wastewater measurement, and exposing them to vocabulary like “dosing,” “turbidity,” and “filaments.” The goal is to stay within permit: operating, maintaining, and treating all incoming wastewater—which entails submitting daily, weekly, and monthly checklists and lab results.